GATHERING Roonstraße 108 Cologne

Gathering is thrilled to announce the opening of its new gallery in Cologne, expanding its presence beyond London and Ibiza.

With this launch, Gathering deepens its commitment to bold, artist-led programming, inaugurating with a solo exhibition by the late Sibylle Ruppert (1942–2011). This marks Ruppert’s first presentation in Cologne since 1971, reaffirming her enduring influence on the European underground art scene and contemporary visual culture.

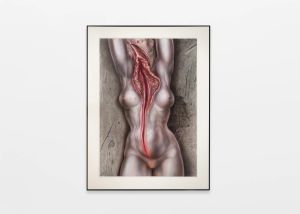

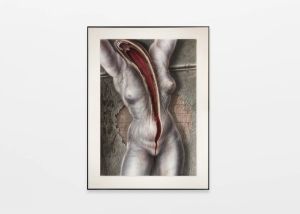

In the work of Sibylle Ruppert flesh appears to liquify into molten metal. Bodies are flayed and turned inside out, exploded into a seething melange of slits, sockets, and musculature bound by tearing membrane. Each figure is presented in a state of violent metamorphosis, split apart and reconfigured into indiscriminate masses of hungry viscera. This world of tumescent genitalia and gaping mouths, delicately rendered in charcoal and pencil, embraces obscenity as its guiding principle.

‘Obscenity’ is given several definitions by Merriam-Webster, including ‘disgusting to the senses: repulsive’; ‘abhorrent to morality or virtue’; ‘so excessive as to be offensive.’ While Ruppert’s work is certainly filled with representations of excess and amorality, it is French philosopher Georges Bataille’s definition that gets to the heart of Ruppert’s mobilisation of obscene imagery. According to Bataille, ‘obscenity’ is ‘our name for the uneasiness that upsets the physical state associated with self-possession, of a recognised and stable individuality.’ In Ruppert’s paintings, drawings and collages, the self is ruptured, even annihilated, through states of corporeal extremity; left in its place is a fractured landscape of libidinal compulsion and terror. As in the work of writer and libertine Marquis de Sade – much admired by Ruppert – the ‘image of the obscene body’ forms a site in which ‘spectatorship is politicised, desire is interrogated, and the dynamic of the dominator and dominated is willingly explored’ (Alyce Mahon, The Marquis de Sade and the Avant-Garde, 2020).

Many biographies of the artist that appear on websites and in press packets start with the same detail: she was born ‘during an air raid on 8 September 1942.’ In this telling, it is as if Ruppert’s being was marked by a special kind of machinic brutality from the beginning, her entry into the world heralded by the heat and destruction of falling Allied bombs. Much of her life – as it is relayed to us now – retains this dark fairytale tenor: during the war she and her family sheltered in the castle of an aristocratic beneficiary; she became a dancer, before immersing herself in the literature of the Marquis de Sade; she died in Paris, withdrawn from public and social life. Indiscreet Jewels marks the first presentation of Ruppert’s work in Cologne since 1971; between 1977 and 2010, the artist’s output went almost entirely ignored. Interest in her work was reignited following a retrospective held by the H. R Giger museum, the year before her death. As a result, discussions of her oeuvre are often appended with comparisons to Giger’s biomechanical visions. As Ruppert garners increasing posthumous recognition, it is important to consider her work on its own terms, situated within a highly considered framework of influences and ideas that do not depend upon Giger.

These influences include the morbid eroticism of the Marquis de Sade, the Comte de Lautréamont and Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, as well as the fantastic visions of Henry Fuseli and William Blake. In their meticulous draughtsmanship, Ruppert’s pencil drawings evoke the strange mixture of fastidious precision and oneiric horror that characterise the lithographs of French symbolist Odilon Redon. We might imagine the writhing, interpenetrated bodies in Ruppert’s work occupying the substrate beneath the moonlike eyeballs and ghostly hierophants that populate the gloaming of Redon’s shadowy realm. La lune violente (1979) depicts a figure’s head and shoulders disassembling into a sebaceous vortex, its shoulders sliced by the sharp edge of a crescent moon; in La fontaine (1977), meanwhile, a Cerberus-like creature is endowed with a tumescent phallic trunk out of which a half-woman erupts. Pour La Anniversaire de B.A (1979) and La Lutte (1977) show muscle-bound bodies fused with metal armatures, recalling Alain Robbe-Grillet’s association of Ruppert’s work with ‘disembowelled horses, stallions with massive muscles, with harrows, butcher’s hooks, and ploughshares.’ Steaming offal, hooks in meat, bodies that break and are forged back together: these images of base corporeality melt into phantasms through Ruppert’s delicate handling of charcoal and crayon.

The works on display in Indiscreet Jewels visualise the entrails of the human psyche, exposed by ‘cutting through the surface of [one’s] own skin and seeking to discover what lies beneath’ (Ruppert, 1995). In giving crystalline form to this ‘beneath,’ Ruppert impels us to borrow her courage: to face the primordial stew of danger and delight that roils hotly inside each of us.

Text by Sybilla Griffin Work Images Courtesy of Blue Velvet Projects and the Estate of Sibylle Ruppert Installation Images by Volker Crone